Why Major Beauty Groups Are Selling Brands and What the Estée Lauder and Coty Cases Reveal About the Industry’s Future

For decades, the global beauty industry was built on a simple and reliable idea. If you owned enough brands across enough price points, channels, and geographies, growth would take care of itself. Scale was protection. Portfolio breadth was strength. Declining brands could be compensated by rising ones. Capital flowed freely, consumers were loyal, and retail distribution created natural barriers to entry.

That era is over.

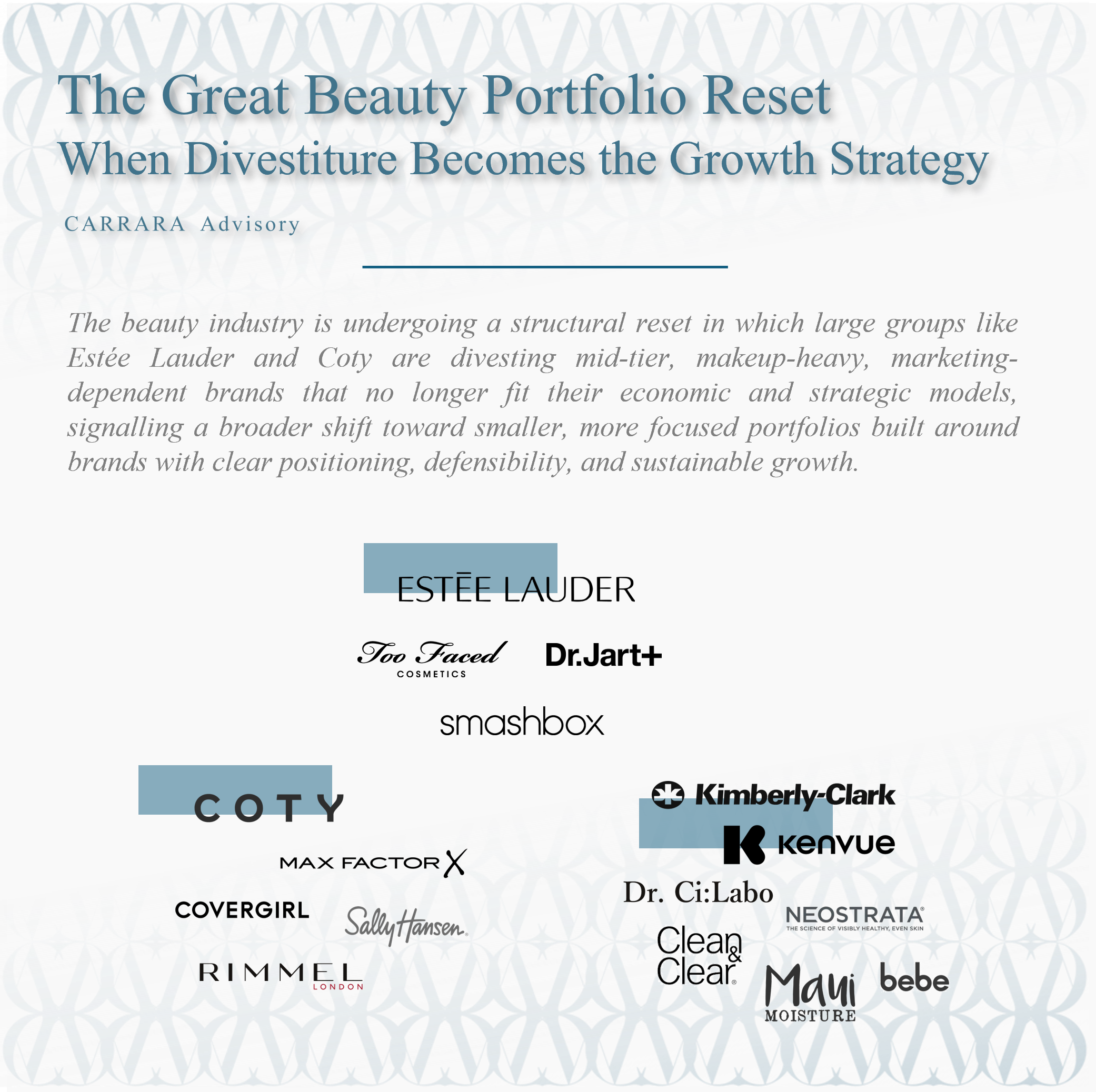

What we are witnessing today is not a cycle. It is a structural reset. Large beauty groups are reassessing what they own, why they own it, and whether certain brands still deserve capital, management attention, and shelf space. The result is a growing wave of divestitures, carve outs, and strategic reviews that would have been unthinkable fifteen years ago.

This trend is not limited to one company or one category. It spans mass and prestige, makeup and skincare, heritage brands and former cult favorites. And it is accelerating.

At the center of this shift are two emblematic cases. Estée Lauder Companies, long considered the gold standard of prestige beauty portfolio management, is actively preparing to sell multiple brands. Coty, after years of restructuring and leadership changes, has openly evaluated selling or spinning off several of its mass beauty brands.

These are not isolated moves. They are signals.

To understand what is happening, and what comes next, we need to step back and look at the broader divestiture trend in beauty. Then we need to examine Estée Lauder and Coty closely. And finally, we need to understand the common characteristics of the brands being pushed out, because those characteristics tell us far more about the future of beauty than any press release ever will.

Part One. The Rise of Divestitures in the Beauty Industry

How the traditional beauty conglomerate model worked

Historically, large beauty groups were built like holding companies with strong operating arms. They acquired brands across different segments and managed them through centralized functions. Manufacturing, procurement, distribution, and sometimes even marketing services were shared. This created economies of scale and protected margins.

The portfolio logic was straightforward. A mix of brands at different life stages stabilized earnings. A declining brand could still throw off cash. A growing brand could absorb investment. Retail partners liked the simplicity of dealing with one large supplier. Consumers tended to stay loyal within brand families.

This model worked exceptionally well in a world where media was linear, retail was physical, and competition was limited by access to distribution.

Why the model is breaking down

Three forces have undermined this structure.

First, the collapse of traditional barriers to entry. Digital distribution, contract manufacturing, and social media have made it possible for small brands to scale quickly without owning factories or negotiating with department stores. This has flooded the market with competitors.

Second, the fragmentation of consumer attention. Brand loyalty is weaker. Trends move faster. What worked five years ago can look outdated today. Large organizations struggle to move at this speed, especially when managing dozens of brands.

Third, capital markets have changed their expectations. Investors no longer reward size for its own sake. They reward clarity, margins, and predictable growth. Brands that require constant support just to maintain relevance are increasingly seen as liabilities, not assets.

The result is a harsh reality. Not every brand in a large portfolio deserves to stay there.

Divestiture as a strategic necessity, not a failure

In the past, selling a brand was often seen as an admission of failure. Today, it is increasingly seen as a sign of discipline.

Divestitures allow companies to free up capital, reduce complexity, and focus management attention on brands with stronger long term economics. They also reflect a more honest assessment of what a large organization can realistically nurture.

Importantly, divestiture does not mean a brand is dead. In many cases, it simply means the brand is better suited to a different owner, one with lower overhead, sharper focus, and a different risk tolerance.

This is the context in which the Estée Lauder and Coty moves should be understood.

Part Two. Estée Lauder Companies and the Limits of Prestige Expansion

The Estée Lauder legacy and its portfolio strategy

Estée Lauder Companies built its reputation on prestige beauty. The group mastered department store distribution, invested heavily in brand storytelling, and built a portfolio that combined heritage brands with newer acquisitions.

For years, its acquisition strategy was praised. Brands like MAC, La Mer, Jo Malone, Too Faced, and Dr. Jart were added at different times to capture new consumers, categories, and geographies.

The underlying belief was that prestige beauty, if managed well, would always justify premium pricing and deliver strong margins.

What has changed for Estée Lauder

Several things have shifted at once.

First, the prestige market has become crowded. There are now far more prestige brands competing for the same consumer. Many of them are founder led, digitally native, and culturally sharper than legacy brands.

Second, consumer behavior has become more polarized. Some consumers are trading up to true luxury, while others are trading down to value or masstige. The middle of the prestige spectrum is under pressure.

Third, Estée Lauder, like all large organizations, faces rising costs and internal complexity. Managing a large number of brands across regions, channels, and categories is expensive. When growth slows, those costs become harder to justify.

Why certain Estée Lauder brands are now being considered for sale

The brands reportedly being prepared for sale share a number of characteristics.

They are not core to the original Estée Lauder DNA. They are not true luxury. They are not delivering exceptional growth relative to the capital they require.

Brands like Too Faced and Smashbox were once highly relevant. They benefited from strong retailer partnerships and cultural moments. Over time, their positioning became less distinct. Competition intensified. Marketing costs rose.

Dr. Jart, while in skincare, also relies heavily on trends and campaign driven visibility. In a crowded global skincare market, that creates volatility.

From a portfolio perspective, these brands no longer fit cleanly into a focused prestige strategy. They require attention and investment that could be better deployed elsewhere.

The decision to sell them is not about quality. It is about fit.

Part Three. Coty and the Reckoning in Mass Beauty

Coty’s complex history

Coty’s portfolio has long been a mix of mass beauty, prestige fragrances, and licensed brands. The company went through a significant transformation after acquiring major assets from Procter and Gamble, including CoverGirl and other mass brands.

That acquisition brought scale, but it also brought challenges. Integration was complex. Some brands were already in decline. The mass beauty market itself was changing rapidly.

Over the past several years, Coty has been restructuring, simplifying, and attempting to sharpen its focus. Leadership changes reflected the difficulty of balancing legacy mass brands with higher growth prestige and fragrance assets.

Why mass beauty brands are under pressure

Mass beauty faces structural challenges.

Retail dynamics have shifted. Drugstores and mass retailers have reduced shelf space. Promotions have intensified. Private label competition has increased.

At the same time, digital native brands have proven they can compete at lower price points with better speed and storytelling.

Brands like CoverGirl, Rimmel, Max Factor, and Sally Hansen still have awareness. But awareness alone is no longer enough. These brands often require heavy promotional support to maintain share, which compresses margins.

For a publicly listed company under pressure to improve financial performance, this becomes a problem.

Coty’s consideration of divestitures

Coty’s exploration of selling or spinning off parts of its mass beauty portfolio reflects a strategic pivot.

The company has increasingly emphasized prestige fragrances and partnerships that deliver higher margins and more predictable growth. In that context, mass makeup brands that require constant intervention look less attractive.

Divesting these brands would allow Coty to simplify its structure, reduce operational complexity, and align more closely with where it sees future value.

Again, this is not about abandoning consumers. It is about acknowledging economic reality.

Part Four. The Common Characteristics of the Brands Being Divested

When you compare the brands Estée Lauder and Coty are considering selling, a clear pattern emerges.

Stuck in the middle positioning

Most of these brands sit in an uncomfortable middle space.

They are not luxury enough to command high prices without resistance. They are not low cost enough to win on efficiency alone. As a result, they struggle to defend their margins.

This middle ground used to be profitable. Today, it is the most dangerous place to be.

Heavy reliance on makeup

Another commonality is category exposure. Many of these brands are heavily focused on color cosmetics.

Makeup has proven more volatile than skincare or fragrance. Trends change quickly. Consumer usage patterns fluctuate. Marketing requirements are intense.

For large organizations seeking stability, makeup heavy brands introduce risk.

High marketing intensity and low defensibility

These brands often rely on constant marketing support to stay relevant. They do not benefit from strong intellectual property, proprietary technology, or deep ritual driven usage.

When marketing spend slows, performance declines. That makes them unattractive in a capital constrained environment.

Heritage without momentum

Finally, many of these brands are former icons. They are well known. They are respected. But they no longer define the category.

Heritage without momentum is a problem for large companies. Nostalgia does not generate growth.

Part Five. What This Means for the Future of Beauty

The end of the bloated portfolio

The beauty industry is moving toward fewer, stronger brands within each group. Portfolio discipline will matter more than portfolio size.

Companies will increasingly ask hard questions about why they own each brand and what role it plays.

A new role for private ownership

Many of the brands being divested are better suited to private ownership. With lower overhead and more focused leadership, they can still thrive.

We are likely to see more private equity and founder led groups acquiring these assets and running them differently.

A return to fundamentals

Ultimately, this trend represents a return to basics. Brands must earn their place. Growth must be justified. Complexity must be controlled.

This is not a crisis. It is a correction.

Conclusion

The divestiture wave sweeping through the beauty industry is not temporary. It reflects a deeper shift in how value is created and measured.

Estée Lauder and Coty are not outliers. They are early signals of a broader realignment. The brands being sold are not weak. They are simply misaligned with the structures that own them.

For operators, investors, and founders, the message is clear. The future of beauty belongs to brands with clarity, defensibility, and momentum. Everything else will need a new home.

And that, in the long run, may be the healthiest outcome for the industry as a whole.