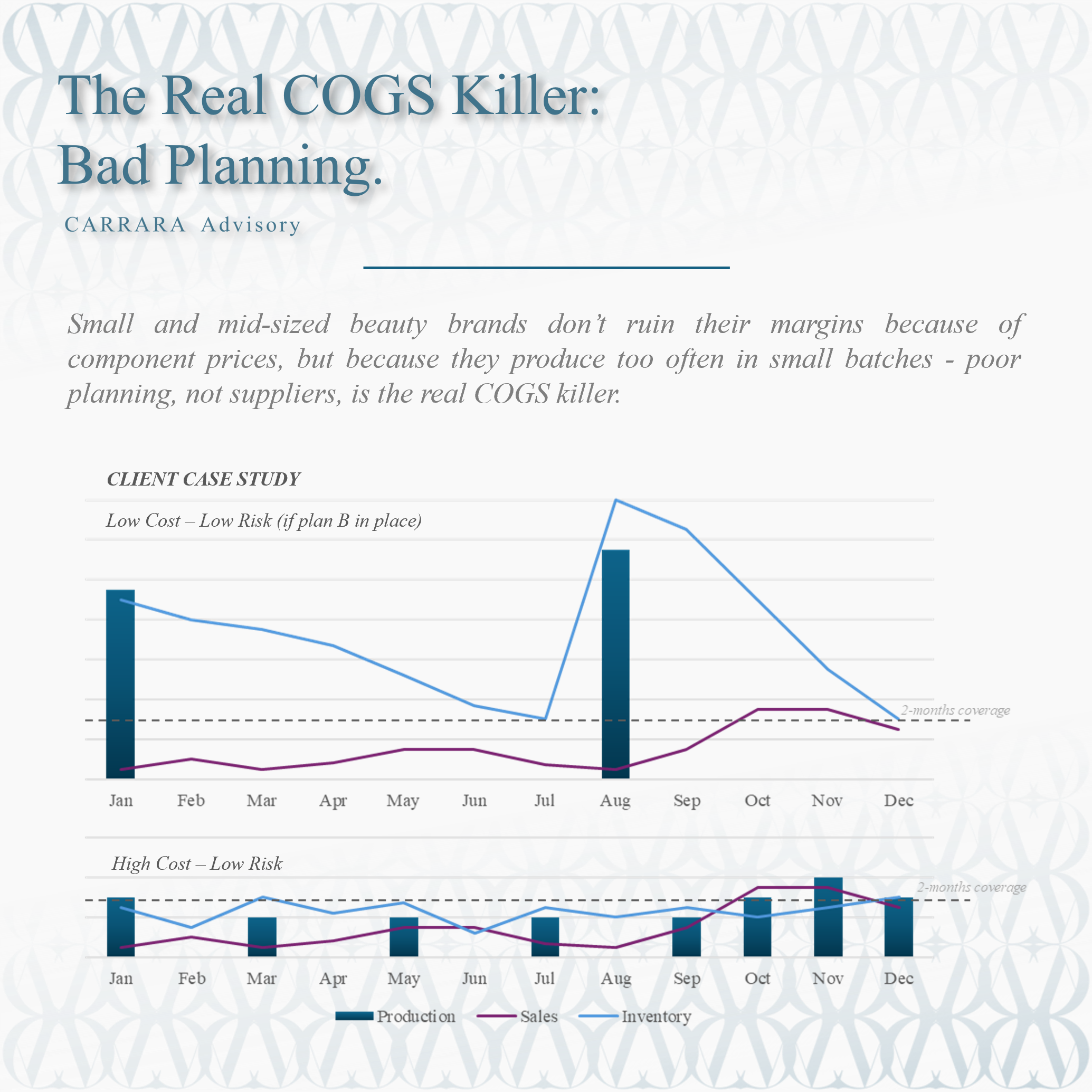

In the second scenario, the brand produces twice per year in larger batches. Inventory builds higher twice during the cycle, then declines, but the amortization and setup costs are spread over significantly more units per batch. Total production for the year is the same. Ending inventory is the same. Sales are the same. Yet the eight-run model carries materially higher cost per unit purely because the operational cadence forces process repetition.

Nothing changed in component pricing, formula cost, (partially) freight, or duties. The only variable was production timing. This is the essence of structural COGS leakage for small brands. It is invisible until modeled, but once seen it is impossible to ignore.

For the specific client, the COGS of the leading SKU, a perfume, moved from an yearly average of 7.12 eur/100ml to 5.33 eur/100ml or a cost saving of 25% without having changed anything from a product perspective.

The economics are driven not by what you buy but by when and how you produce.

Closing observation

Most founders never discuss amortization, cadence, and planning discipline because these topics don’t make for romantic brand folklore. They don’t sparkle in pitch decks. But they make or break financial viability.

COGS is not a vendor outcome. It is the arithmetic reflection of operational maturity.

For small and mid-size brands, low volumes and immature forecasting create real amortization penalties. This is where production cadence becomes the decisive lever. When you produce too often, you pay setup costs multiple times. When you produce too seldom, you invite stockouts and emergency costs. The middle path is where sustainable unit economics live.

It is important to clarify this: for large brands operating at consistently high volumes, the dynamic shifts. Once the line is always running at optimal efficiency, amortization stops being the constraint and cash flow becomes the management priority. In those cases, more frequent production can be beneficial. But that is the privilege of scale. You earn that advantage; it is not available to small players.

For accessible brands and challenger beauty houses, COGS is not a “supplier problem”. It is an internal posture. It lives in forecasting, in SKU-specific planning, in disciplined decision making and in the willingness to manage inventory strategically rather than emotionally.

Great brands do not negotiate pennies. They build the operational habits that generate dollars.

And when they do that, they stop being at the mercy of emergencies, freight premiums and last-minute scrambling. They start controlling their own destiny.

And that is why the real competitive edge in accessible beauty is not marketing bravado but disciplined industrial thinking. That is the difference between brands that merely exist and brands that survive time.