Performance: The Financial Backbone of Kering’s Transformation

Introduction

Over the past two decades, Kering has undergone one of the most profound transformations in the luxury industry, evolving from a diversified retail conglomerate into a highly focused house of global luxury brands. This strategic metamorphosis has not been a straight line, but rather a series of deliberate pivots: divestitures of mass-market and retail operations on one side, and bold acquisitions in high-value segments such as fashion, jewelry, and fragrance on the other.

In this second part of our three-part series on Kering’s evolution, we turn to the financial foundations that underpin this transformation, examining how changes in net indebtedness, goodwill, and working capital mirror the company’s shifting priorities. While Part I focused on the strategic and organizational transitions, this analysis interprets the numbers behind those moves: how acquisitions, sales, and strategic refocus reshaped the Group’s financial posture and capital structure.

Taken together, these financial dynamics offer a revealing view into Kering’s long-term trajectory, a company continually balancing ambition and prudence, reinvention and discipline. For readers interested in the historical and strategic context behind these figures, Part I provides the groundwork for understanding the rationale that drives the numbers we now explore.

Profit and Loss

Over the past two decades Kering’s profit & loss tells a two-act story: a structural shift in business mix from diversified retail and lifestyle activities toward concentrated, high-margin luxury houses, and, more recently, the limitations of that strategy when top-line momentum falters. The data show that reported net sales moved in waves rather than along a steady growth curve: roughly €27.4 billion in 2002 (reflecting the company’s broader, pre-luxury focus), a fast decline till 2005 due to Rexel and financial services divestitures, and then again till 2012 with the complete exit from the retail business. Then the growth of luxury division becomes more apparent, with an apparent peak around 2021 at ~€20.4 billion, and then a drop to €17.2 billion in 2024.

At the same time gross margin rose in absolute terms from about €10.6 billion in 2002 to roughly €15 billion in 2022, while the gross-margin ratio climbed dramatically from the high-30s percent to the low-to-mid 70s percent by 2018–19.

That margin expansion is the single most important structural fact in this P&L. This is not a small operational tweak, it is the arithmetic result of a portfolio that now tilts overwhelmingly toward luxury houses with meaningful pricing power and low variable cost per unit of perceived value.

As the share of revenues coming from the Luxury division climbs from roughly 10% in 2002 to over 90% after 2017, the gross margin moves in lockstep from the high 30s to the mid-70s. It’s an almost perfect correlation: every percentage point increase in luxury exposure has translated into higher structural profitability. But that same linearity also warns of saturation: once the portfolio is already 90%+ luxury, the margin can no longer expand structurally; the lever is spent. Future margin movements will depend not on portfolio mix but on brand performance and pricing power within that already-luxury base.

In other words, the line that once symbolized strategic progress now also marks the limit of that strategy’s mechanical benefits. From here on, margin protection will come from execution, creative renewal, distribution discipline, and cost control, rather than portfolio composition.

The brand-level splits make the mechanism obvious: Gucci grows from €1.58 billion in 2002 to a peak of €10.5 billion in 2022; YSL and Bottega Veneta evolve from minor contributors into mid-single-billion euro houses. As the higher-margin luxury mix replaces lower-margin retail or mass segments (divested during the period), gross profit as a percentage of revenue surges even when absolute revenues stall or decline.

But margins can be a two-edged sword. High gross margin with falling sales creates negative operational leverage: fixed costs (store networks, marketing, product development) and investments in distribution remain, while the top line shrinks, which can wipe out operating leverage quickly. That is exactly what Kering warned investors about in 2024: group revenue was €17.2 billion in 2024, down 12% both reported and on a comparable basis, and management flagged negative operational leverage due to weaker sales at Gucci and some other houses. The company’s public statements and filings emphasize the pain point: the group’s 2024 sales decline was concentrated in its flagship houses and in wholesale, while certain businesses (Eyewear, some Jewellery) still grew.

Brand dynamics explain much of both the upside and the present vulnerability. Gucci historically accounted for a very large share of group revenue and an even larger share of operating profit: this concentration delivers outsized margin benefit when Gucci is firing on all cylinders, and outsized pain when the label is weak.

Notably higher gross margins can buy time for investments and repositioning, but only if the company can quickly right-size fixed costs or repurpose investments; otherwise negative operational leverage will bite (as Kering experienced in 2024, with guidance cuts and investor alarm).

The margin ladder over time (from gross profit to EBITDA to net income) tells a sharper version of the same transformation shown in the previous charts, but it also highlights the limits and vulnerabilities of Kering’s model.

Structural Margin Expansion

Between 2002 and 2019, Kering’s profitability profile underwent a remarkable structural expansion. All three key margins, gross, EBITDA, and net, moved upward in concert, revealing both the success of the group’s portfolio transformation and the power of operating leverage within a luxury model. Gross margin nearly doubled, rising from around 39% to 74%, reflecting the steady shift from lifestyle and retail businesses to high-end brands with strong pricing power. EBITDA margin, meanwhile, more than quadrupled, climbing from roughly 8% to 38%, demonstrating that Kering did not merely sell higher-margin products but managed to retain a significant share of that added value through disciplined cost control and operational scaling. Net income margin followed the same trajectory, growing from the low single digits to peaks near 19% (2019 depression was due to one-time tax settlement in Italy), signaling an unprecedented capacity to translate sales into bottom-line profitability. This phase, particularly between 2017 and 2019, represents the apex of Kering’s operating leverage: once the fixed costs of its global retail network and corporate structure were covered, incremental luxury sales converted disproportionately into profit, amplifying the group’s earnings power during years of synchronized brand performance.

Margin Compression and Volatility (Post-2021)

From 2019 onward, however, the picture changes. The same leverage that once magnified profitability began to work in reverse. While gross margins remained above 70%, both EBITDA and net income margins contracted (sharply in 2024), with EBITDA falling from around 38% to 27% by 2024 and net margin collapsing from nearly 19% to just 7%. The decline in operating and net profitability was thus far steeper than the mild erosion in product margins, underscoring that the issue was not pricing or cost of goods, but rather the mechanical effect of negative operational leverage. In a structure built for sustained growth, with extensive retail footprints, high creative and marketing expenditures, and limited short-term cost flexibility, a softening top line has an outsized impact on profitability. The result is a margin profile that remains structurally elevated compared to the past, yet increasingly volatile and sensitive to sales fluctuations, the downside of running a luxury model optimized for perpetual expansion. To understand how this profitability pattern was financed and sustained, we turn to the balance sheet, the mirror image of Kering’s operational evolution.

The Luxury Trade-Off

The pattern proves that luxury delivers high margins, not margin stability. In the growth phase, Kering’s model converts pricing power into superior profitability. In downturns, however, the same structure amplifies downside pressure, EBITDA and net margins swing more violently than gross margins. The 2023–2024 compression is therefore not an accounting accident; it’s the visible consequence of relying on a handful of brands for most operating income.

What this ultimately shows is that Kering’s “margin engine” has reached its structural peak. The group cannot push gross margins much higher (the luxury mix is maxed out) so sustaining profitability now depends on rebuilding top-line momentum and rebalancing cost elasticity. Future improvement will have to come from productivity (store efficiency, shared platforms, digital leverage) rather than from mix shift.

Operating Income by Luxury Brand

Looking at the operating income margin breakdown within Kering’s luxury division, several patterns emerge that tell a very clear story about brand-level performance and the evolution of the group’s portfolio strategy.

First, Gucci dominates both historically and structurally. Its margins are consistently high, starting around 28–29% in the early 2000s and peaking above 40% by 2018–2019. This reflects Gucci’s long-standing strength as Kering’s profit generator: strong pricing power, global brand recognition, and efficient operations allow it to convert sales into operating profit at a very high rate. Gucci’s performance largely drives the overall luxury division margin, which explains why the aggregated luxury margin closely tracks Gucci’s trajectory over time.

In contrast, Bottega Veneta and YSL exhibit a classic “growth and turnaround” pattern. Both brands start with negative or very low operating margins in the early 2000s. Bottega Veneta turns positive around 2005, then ramps steadily to the mid-30% range before showing some margin softness as of 2014, likely related to increased investments in expansion. YSL’s turnaround is also dramatic: from deep losses in the early 2000s to positive double-digit margins by the mid-2010s, highlighting successful brand repositioning and revitalization initiatives, including high-profile product launches and marketing campaigns.

Other Luxury brands, which include smaller labels (e.g Balenciaga) show more volatility and lower margins overall. They oscillate around breakeven to low double digits, and even decline into negative territory in 2024. This underscores that outside the marquee names (Gucci, Bottega, YSL), Kering’s smaller luxury properties contribute unevenly to profitability, and can be disproportionately affected by investment cycles, market trends, or economic shocks.

If the P&L captures the momentum of Kering’s transformation, the balance sheet shows the architecture behind it; how growth was financed, assets deployed, and risk managed.

Balance Sheet Dynamics

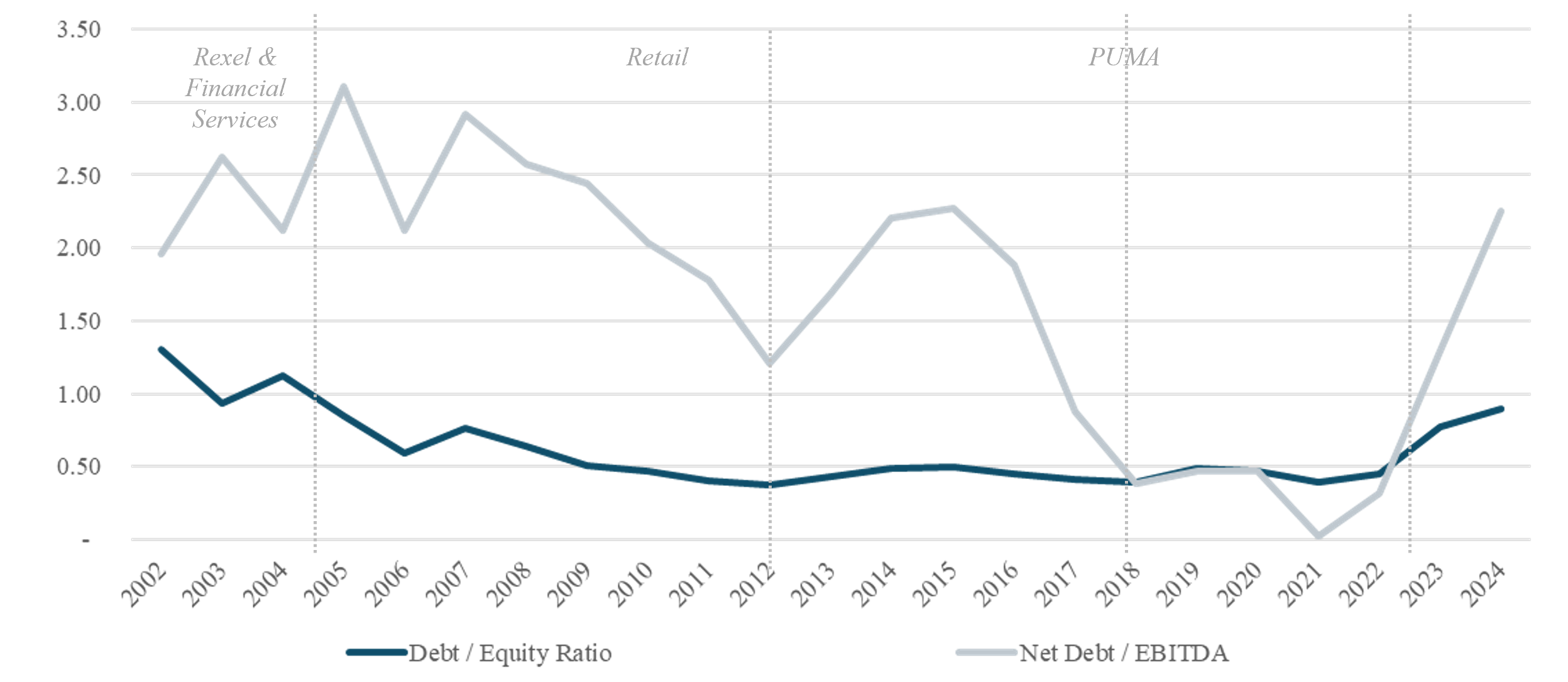

Understanding Kering’s trajectory requires more than tracking its income statement: the balance sheet tells the story of how growth was financed, where capital was deployed, and how efficiently those resources generated returns. Over two decades, Kering’s balance sheet transformed from a mixed retail–luxury structure into a streamlined, brand-centric luxury group; an evolution visible across liquidity, leverage, asset composition, and capital productivity metrics.

Liquidity and Short-Term Solvency

The group’s liquidity position has generally strengthened since the early 2000s. The ratio of cash and equivalents to current liabilities climbed from roughly 0.2x in the early years to improving notably during the 2009 financial crisis and again between 2017 and 2019 to reach around 0.4–0.6x in the mature luxury phase (2017–2021), showing a deliberate shift toward stronger cash buffers and financial flexibility. Since then, liquidity has moderated as investments in retail networks and brand elevation absorbed more working capital. This evolution mirrors the strategic derisking that followed Kering’s exit from mass retail.

Working capital composition, however, changed markedly. The Inventory-to-Receivable ratio expanded steadily from around 1.0x in the early 2000s to nearly 4.0x by 2024, showing that Kering’s asset base has become increasingly dominated by stock rather than trade receivables. This reflects both the nature of the luxury model, where wholesale gives way to direct retail, and a structural increase in inventory intensity. It also suggests greater exposure to demand cycles, as unsold products now represent a larger share of short-term assets.

At the same time, the inventory days-to-receivable days ratio (DIO/DSO) expanded sharply, from below 2x in the early 2000s to more than 15x by 2024, a reflection of the group’s capital commitment to store networks and slower-moving luxury goods. The trade-off is typical of the luxury model: greater control over distribution and product availability, but heavier working capital requirements.

In fact if we do plot inventory days-to-receivable days ratio (DIO/DSO) against the number of directly operated luxury stores we see three different clusters:

In the early 2000s, Kering (then Pinault-Printemps-Redoute) was a diversified holding spanning retail (Printemps, Conforama, FNAC), electrical distribution (Rexel), and financial services. DIO/DSO ratio ~1.7–1.9 means that inventory and receivables were relatively balanced, a typical structure for a mixed portfolio with both fast-moving retail and wholesale distribution. In this phase, working capital was relatively efficient because: the retail and distribution businesses turned over stock quickly (low DIO) and receivables were moderate but stable, reflecting short credit cycles in consumer goods and B2B distribution. In short, this cluster reflects a multi-sector group with efficient turnover and modest luxury exposure.

The second cluster (2005-2015) reflects the period when Kering had retail (FNAC, Conforama), lifestyle (PUMA, Volcom), and luxury brands (Gucci, Bottega Veneta, YSL). DIO/DSO rises from ~4x to ~6x, with a steep slope as the number of directly operated luxury stores expands from ~400 to 1,200. This slope represents a transitional phase, as the group pivoted away from general retail and distribution towards lifestyle and luxury, its inventory model fundamentally changed.

What’s happening here is a mix effect:

PUMA and other lifestyle brands increased DIO due to slower inventory rotation than mass retail but still had significant receivables from wholesale customers (hence the steep DIO/DSO rise).

At the same time, luxury’s growing share brought higher inventory values per store (each boutique carrying more high-value, slow-moving items).

Retail expansion amplified this effect, as each new luxury store required stock allocation, visual merchandising, and local assortments, all before sales maturity.

So this middle slope shows the structural drag of shifting from turnover-driven retail to margin-driven luxury, high growth, but progressively more capital tied in stock.

After Kering divested PUMA (2018-2024) and the remaining lifestyle assets, the group became a pure luxury player. Stores increased from 1,300 to over 1,800, but DIO/DSO surged more moderately, from ~11x to ~15x. The slope flattens because, once the model stabilized around full control of distribution (retail vs wholesale), incremental stores did not change the working capital structure as dramatically.

Now, the higher absolute DIO/DSO ratio (around 15x) signals a mature luxury balance sheet:

Luxury retail operates with inherently slow stock rotation (high DIO).

Receivables are minimal since sales are largely direct-to-consumer (very low DSO).

The ratio therefore inflates, but not because of inefficiency, rather, because the business model shifted from wholesale cash cycles to owned retail and brand control.